By Melo Anon

With the story finished, or at least outlined, departments like art and programming can start looking through and planning out a list of assets and cues. The same goes for music; sometimes a writer might put in music cues or request certain tracks be played, usually at a key moment in the story, but often it’s up to the composer to decide how music will play in the overall narrative. Even so, your job as a musician starts before this, as you have to decide how this game will sound, all before you write any music. This article isn’t about how to make music, as I’m sure you already know how if you want to make music for a game. Instead, it’s about using your skills as a composer and planning out the soundtrack, and the process of doing so.

Genre

In this DAW age of endless possibilities in sound design and songwriting, a composer isn’t limited to the genre stereotype of “Video Game Music”, which means less as the years between now and chiptune soundtracks of the NES continue to grow. Genres can help defy the sound of a game, creating unity between tracks, but these can always branch off into fusion and microgenres later down the line. There’s nothing wrong with sticking to cliches, like Country music for a cowboy setting, or Hard Metal for a game set in the depths of Hell. However, a diversion from genre norms can let your music stand out from the others. Thankfully, a visual novel is a genre that lacks any traditional “gameplay”, so you as a composer are more free to experiment, using tracks to fit environments and emotions instead of set pieces. Make and share a playlist of the kinds of genres you’re trying to tackle. If it’s your aim to create something new and something unique, try avoiding listening to music when writing.

Types of Tracks

There are generally two types of tracks you’ll have to decide on when writing up a list of songs; General and Event tracks. General tracks are like default sprites, made to be used as much as possible, usually in non key moments of the story. However, these don’t always equate to basic background ambience, as music can help set the mood of a scene. Play any narrative game and you’ll spot that “Sad” and “Happy” track, themes that are used multiple times to elicit or reinforce a desired emotion. The same goes for your casual tracks; upbeat and chill music that fits the “vibe” of a scene. This of course depends on the type of story you’re telling, if this world is dark and depressing you might want to switch out upbeat with melancholic and chill with haunting. It’s good to have multiple versions of these casual tracks, as you’ll be using them alot, especially when the story calls for a “slice of life” situation.

Character Themes

Next are character themes, which is usually where motifs come into play. Motifs, whether they are instrument or melody based, can be used for simple tasks like establishing the “sound” of a character, or in more clever ways, like following an important scene in the story.

Eagle-eared listeners of Wani’s soundtrack may have noticed Iakadan’s motif being used most prominently in Ending C, as the effects of his death are addressed by Olivia and Inco.

Not every character needs a theme, major or minor, and when it comes to reading the script, you can determine if a theme is needed or if a general track might work instead.

Area Themes & Others

Depending on your preferences, you may want to have some area themes as well, like a school or work theme; a track that plays whenever characters are in that location. These can be both one off and recurring, and be treated like your casual tracks.

As a composer, you have the freedom to decide when and where music can be used, but knowing when to use music is as important as knowing when not to use music. Sometimes silence, straight or just ambience, is the answer. Lastly, there are the more technical tracks, your menu song and whatnot. A menu track is what the player hears for the first time, and is essentially the game’s theme. The music here can be a good setup for what’s to come, and establish the “sound” of the soundtrack.

Event Tracks

Event tracks are most of the time one off songs, saved for special moments in the story. Using a new song instead of a general track can add more drama to the situation, or hint at an importance of a future scene. One might be inclined to only make event tracks to reduce music fatigue, but you’ll eventually overload the player with too many tracks and more importantly, lose the effect a special song might have on a scene. Often, these event tracks are what players remember, and come back too, days to even years after finishing the game. They reinforce the memorability of a scene, making your song even that more special. A motif works beautifully here, like the aforementioned dance track, which plays during a special very special; an animated one.

Music for a cutscene involves the more classic form of composition, much like that of film and television. You’re following beats, syncing the music with the actions of the animation. Often, you’re forced to work more free-form, off of the quantization grid, but with the non linear environment of a DAW, you can easily move tracks around to fit in time with the action.

You, The Music Maker

It’s important for you and your team to know your own tastes and abilities musically, whether it be your setup and/or skills as a musician. You might work with samples, acoustic instruments, or a hybrid of both and many more. Learning and growing as an artist is always beneficial, but chasing certain sounds and perfection can often lead to creative burnout, and is not always feasible when working on a deadline. This can be rough when you’re the sole musician, but if you’re working with others, discussing your strengths and weaknesses can help in splitting the workload. Ask yourself what kind of music you enjoy listening to, what kind of music you enjoy making, and what kind of music you want to make.

Of course these should all fit with the theme of the game, as discussed in the previous Genre section. Plan your work accordingly, don’t spend all your energy on one track when you could have spent that time on three or four. Don’t be afraid to say no to an idea, but always offer an alternative.

The List

Writing up a list of tracks can seem like a daunting task at first but it saves you from the stress of forgetting about a track days before you’re set to release. Likewise, noting down where these tracks will play according to the script lets you account for how many times a track is used, and how to easily avoid track burnout. However, you will still need to adjust the timing and length of tracks when the game is compiled, as there is always a difference between reading the script and playing the game. Most importantly, this list can help plant the seeds of ideas when it comes to writing a track. There is no better feeling than reading an important part in the story and imagining a the track that could fit. If the script is being written on an online, collaborative site such as Google Docs, you can easily copy it and write down notes write on the script itself.

If you find yourself writing down a lot tracks, probably more than you can handle, separate them into two categories, A and B. A, for tracks that definitely need to be in the game, and B, for tracks that could work, but could also just be replaced by your general tracks. Once you finish all your A tracks, you can start work on a few B tracks, if you have the time of course.

The Writing Process

Part 1: The Demo

A demo can have many forms and multiple versions, but in the end its purpose is to present a working idea to the rest of the team. This can be a melody, a motif, or even a near finished track. Feedback in the early stages is important, especially when a track you’ve spent so much time on ends being rejected. These demos can come at almost any point in the creative process, both when recording and planning your tracks. Experimenting can help you find the sound or genre you’re looking for, and give an example for the others. Here you don’t have to worry about mixing or for things to sound perfect, as you might switch out an instrument or go in another direction.

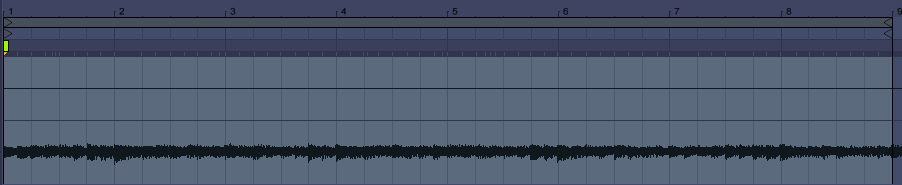

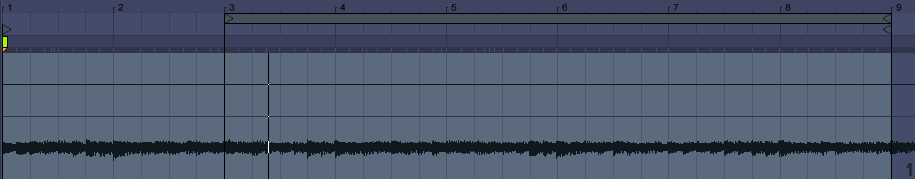

Sometimes you’ll go through multiple versions, some similar, some completely different, shown here with the multiple demos of One Last Favor, which gradually morphs into the finale version heard in game:

This early stage of the writing process is partly trial and error, as you try to figure what sticks and what doesn’t. You might work on one track a little bit then move on to another, following whatever inspiration may come your way. Despite the relevance of event tracks, general tracks are more important, as they cover most of the game. Starting with these can help alleviate the workload later down the line.

Part 2: The “Second” Draft

Your second, or third or whatever draft is often the finished track, minus mixing and other fixes, compiled by feedback from the team and your own input. It’s here where you have decide where the track loops, and how to let that loop go unnoticed. With General Tracks, repetition isn’t too much of an issue as these are mostly background music, maybe a little catchy, but not too grand that it overpowers what might be a casual scene. But Event Tracks are where you really have to think about timing and variety. There’s nothing worse than taking the player out of an important scene with some obvious loop.

Most DAWs have a loop feature, which lets you repeat a point in the timeline, use this at the start to get a sense of the track, and make sure there’s a good transition between where the loop starts and repeats. The easiest route to looping is to loop back to the beginning, but if your track has an introduction, its main melody coming in later, you’ll have to note down your Loop Point. This should be calculated in samples, not in seconds or milliseconds, as this point has to be precise.

This is where feedback is important, and context is needed for the track before you can finish it. Having fresh ears on a track that you’ve spent hours on can help point out mistakes you might blocked off after hearing the song over and over again. Is the melody long and varied in this event track that it goes practically unnoticed when playing the game? These kinks can be ironed out and over time, so eventually you’ll have a version you and the team are comfortable with.

Part 3: The Finale

This is the final track, the song that goes in the game. Here you make any other small adjustments, and do your mixing and mastering. Since most of us don’t have access to a properly treated music studio, we have to do with the speakers and/or headphones we have. (I recommend at least good quality headphones). Don’t feel too pressured, since most people are going to play the game with earbuds and headsets. Your main focus with mixing is to make things less muddled. Use panning, EQ, and other tools to let the instruments breathe and be heard. Fix any tonal issues or audio mistakes, which most often than not are pointed out by other listeners. Finally, keep most tracks at a relatively normal volume; you don’t want the player having to go in the settings each time a song changes to either turn down or turn up the music.

It’s good to not leave this step until the end, as no track should be “good enough” when you’re strapped for time. You don’t want to risk leaving mistakes or diagnosing export issues only days before release, and worse, you’re left with a half-baked song that could have sound so much better. But, once you’re done, you can relax with the satisfaction of finishing a song and making it perfect, then letting it be.

Looping

When I started work on Exit 665 and later I Wani Hug That Gator, I had to learn how to properly loop a track. I naively believed that if the track looped in the DAW, it would loop in any other program. This was not the case. Instruments and effects have decay, and while they might sound fine in your program of choice, you will still have to account for that obvious cut when it loops after export.

Even if you’re only working with virtual instruments, make sure you always have control over the decay of a sound. Reverbs and delays are often the big culprit, so an easy solution is to simply turn them off at the start and end of a loop. Make sure to export at the same sample rate as your project, or you’ll run into a loop that is just slightly off, usually resulting in an annoying “click” sound.

Delivery, File Organization, and Archiving

Delivery

Different file formats and sample rates will come into play once you’re ready to export, so it’s good to know when to use which. It’s a lot like taking a picture; You have your original RAW file, large and uncompressed, which you use for high quality prints. Then you have your PNGs and JPEGs, compressed, smaller files both in file and image size, which you upload online and share with family and friends.

For myself, I always export my demos at 44,100 Hz (44k), 16-Bit quality, usually in a .wav or .aif file format. This is what most folks refer to as “CD Quality”, as it’s the quality of a compact disk. Then, I convert the track to a .ogg Vorbis file, which lets me compress the file size, letting me send it over a service like Discord or Matrix, (If your DAW lets you export directly to .ogg, you can skip this step). Sometimes (especially since Discord lowered their file size limit from 25mb to 10mb), I’ll have to reduce the quality, but thankfully the heavier compression isn’t that noticeable.

For the final track, I’ll export it at my DAW’s native sample rate; 48,000 Hz (48k), 24-bit. This is the uncompressed, “raw” file that in most cases won’t actually be used, but serves as the unaltered record of the song. Usually I convert this to FLAC, as it’s a lossless format, as its advanced compression algorithm reducing it’s file size while being identical to the original.

File Organization

Ideally, your team would have set up a service like Google Drive to share and organize files, which means making your own hierarchy of folders, so you and others can easily search for tracks in the future. For example; you have a folder for all the demos, and subfolders for each track, so if you or someone else were looking for a track, they wouldn’t have to scroll through a long list of version 3s and alternative takes. You may want to export soundtrack versions of your tracks that aren’t meant to loop, but instead end like a typical song or simply fade out. Now it’s up to you to decide where this soundtrack folder goes, either with your game tracks or in a seperate folder for merchandise.

Archiving

One benefit of only working with virtual instruments is that you’re already “writing down” your notes and recalling your settings while making the song. While you don’t have the same luxury when working with external instruments and effects like guitars, synthesizers, and pedals, there are still many ways to note down and save down knob positions and tabs, both old-school and modern. You start with naming your tracks, usually just the name of the instruments and some additional information, for example; Nord Lead (The Synth) 42 (The Patch Number). If dealing with a certain setting you tweaked in, make a note of it or take a photo, but make sure to caption it with what it is and which song/track uses it.

Luckily, gear that supports MIDI means its supports Sysex, essentially the language used to communicate and transfer information between two midi devices. Using a sysex tranfer program like Sysex Librarian (Mac), MIDI-OX (PC) and amidi (Linux), you can easily save a synth or effects patch to your computer and recall it when needed. The big benefit of this is that it saves you time from having to manually tune each knob when you need to re-record something. Plus, most of these programs are free and easy to use.

Backups are almost essential for any creative work or work in general, as we can run into problems at any point. Some of these can be minor like computer crashes, but never rule out the possibility of a corrupt file, hard drive, or even worse, a house fire. Have at least one external backup of your projects and recordings, including demos, preferably online. Write down or use notation software to saved your songs and melodies for later, or turn them into sheet music and tabs for other musicians to play. If even nothing bad happens, you still have a copy of all you did.

Releasing Music

After the game is finished and published, you may want to release the music on a service like Bandcamp, streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music, or even physically. Both have their advantages and disadvantages, facts important to know depending on your needs.

Bandcamp is the favourite of most indie musicians today because of its ease of use and “grass roots” approach to selling music. It’s as simple as uploading your songs, giving it a price (Bandcamp only takes a small commission), and making it public. Its support of high quality music files appeal to audiophiles and any music listener wanting the best possible way of listening to your tracks. However, most people don’t use Bandcamp, or only do in rare circumstances.

Streaming for a while now has become the norm, as it’s a way of finding and listening to new music without having to pay anything more than a monthly subscription fee. You just simply find the song you’re looking for and press play. Despite the longer process, releasing on streaming lets you reach a wider audience, and make it easier for fans to listen to your soundtrack. However you have to use a distribution service to release on streaming platforms, and most of the time you will have to pay.

Choosing a distributor might seem daunting, but it’s always good to go with the one that fits your needs the best. If you release music a lot, it might make sense to go with a service like Distrokid, not having to pay every time you put out a song If you only plan on releasing this soundtrack and nothing more for a while, than a service like CDbaby with it’s per release pricing structure is the obvious choice. Different services will have different fees for each stream and might come with different features too, like support for high quality music files and marketing. Despite the wait time, you can be assured that the soundtrack is put on every streaming service, including the more obscure ones and even release on digital music marketplaces like iTunes.

Streaming will always get you more listeners but pennies compared to selling directly to fans. Ultimately, the best option is to do both. You let fans support you and give them the easier option to listen to your music. There are always other ways of distribution as well, like Youtube, Steam and Itch.io. You can even give or sell the music yourself, through your own website. A physical release, whether on CD, Vinyl, Cassette, Minidisc, etc, can be a costly endeavor. Wani’s soundtrack is over 3 hours long, which means the whole thing could only fit on multiple CDs and records, raising the price both for yourself and your fans. While it’s cool to have, it’s not always the best economical choice.

Afterward

During and after my time working on Wani, I learned a lot of things, and ran into some issues. It was definitely a learning curve, especially when going from a few tracks for Snoot Game to a whole dang triple album’s worth of music. Many of rules and lessons I wrote about here I didn’t even follow; in a way I was writing the guide as I went along. Tracks like the School themes and Olivia’s theme ended up being used way less than I thought, both due to their tonal qualities, and because my notes on the script were made after I wrote the tracks.

Olivia’s theme only plays for a few seconds in game, as to fit with her fast introducing and exit in the scene. While the school theme fits well in the opening, it’s a little too upbeat for the more mundane moments in school. A prime example of why listing where your track will play is as important as writing it. The silver lining was that I learned first hand what works and what doesn’t, what you can leave for the end and what you should always start with.

Even after you read this, don’t expect things to always go as planned. Musicians might leave, stories might change, and things just might break. It’s your job to adapt, and stick to a plan, leaving you more time to do what you do best; write music.

Please leave any questions or advice in the comments, I will do my best to respond in a timely manner. And I’m pleased to announce the May 2nd release date of the Side C soundtrack on Bandcamp, and hopefully in just a few days, it will be up on Steam and your streaming platform of choice.

Thanks and happy May,

Melo Anon

Leave a Reply